Octovexillology I – Motivation & Origins

This is the first in a series of articles describing a type of “graphical group identification device” known as “ovexes” (singular “ovecs”), as used in the world of Pasaru. In this article, we describe how these flags came about in the world, and some basic definitions that will be used throughout the series. Other articles in this series will describe in detail how these flags are designed, made and formed into a complex language to themselves.

Octovexillology, as its name suggests, is the study of octagonal flags (even though it is technically the words indicate that it is the study of eight flags). Although the term is fairly generic, it actually refers to a particular type of “flag” which, instead of being a cloth rectangle, is instead a wooden octagon. The origin and evolution of such flags is highly important to its creation, and so we will use this article to laying the groundwork as to how these flags came to be.

In later articles, we will discuss what those flags are in concrete terms, and also what they mean when they start being put together.

1 Overview

1.1 Motivation

With the existence of society, several things are inevitable. These are the existence of groups; the desire to note the existence of such groups; and eventually, as writing is invented, the desire to graphically identify these groups. Such is the case, the desire for graphical group identification device is thus a natural consequence.

On Earth such a desire is in modern times resolved by the use of flags. These are typically rectangular cloth objects that can be hung at very high locations permitting visibility from a long distance at least as long as the wind holds. These come from a rich history of European art known as heraldry, which come with it a particular language that is difficult to express but nevertheless learnable by any human and therefore can brought upon by the rest of the world. However, even on Earth, the desire for group identification devices is too universal for just one civilisation to cover and so there are far more than one way to make these devices.

So when it comes to creating a world that is nominally unrelated to such cultures, it would seem unusual for the peoples of this world to also use a rectangular cloth flag for the usage of a graphical group identification device. It would seem more natural for them to have evolved a different solution, one that has overlapping but different needs. The idea of an ovecs is derived from such an expectation, where we have left some ideas the same from Earth but tweaked small parameters so that the outcome is distinct but nevertheless recognisable. It should be reasonably expected that, should the proverbial butterfly’s wings flapped just that slightly differently, Earth itself might have ended up with these flags.

Furthermore, explaining the history of such a process in this world should inspire the reader who also builds worlds to consider this as an additional dimension as to their While a lot of the details in this series of documents is motivated by the ideas that language-oriented worldbuilding generally spawns, the result should be easy enough to enjoy for anyone of any discipline.

To fully appreciate the setting, we first need to briefly describe the world that surrounds the flags, and how this would have changed things. We will make some reference to the Drsk grammar here, as there is rather a lot of overlap of material between the grammar and this document, and this series of articles is to some extent spun off from that book as it has become somewhat too long and tangential to the main topic. However, it is not necessary to have read the Drsk grammar to any level in order to understand this article.

1.2 Conventions

Unless otherwise stated, these statements are used throughout this series, which affects the reading of certain words.

- All numbers are in decimal (base 10).

- The word “flag” may be used to mean either Earth-style flags

or ovexes depending on the context.

Which is meant can be determined by context.

Should context not be sufficient,

specialised terms will be used:-

- “Ovecs” specifically means the subject of this article;

- “Rectangular flag” specifically means the type of flag the typical reader is likely to be familiar with, specifically referring to Earth-style flags;

- Alternatively, “*flag” may be used as an alternative to “ovecs”.

- The metric system is in use.

- The present day in either world can be assumed to be more or less the same æsthetically and functionally, and is equivalent to the more or less 50 years surrounding the year 2000.

- Non-English words not otherwise labelled are in Egonyota Pasaru, which is abbreviated “E.-Pasaru”. The word “ovecs” is an English word for the purposes of this article.

Throughout this series we will encounter “citations” of the form (a|b). This refers to a set of notebooks that contained the original description of ovexes. Citations in the form (a|b) means that the original text can be found in book a, page b.

2 The world

To give one more insight as to what kind of individuals1 would be using this particular sort of flag, we will need to provide context as to what world they live in and what they are, in a physical sense. In this section, we will briefly describe all of these, especially in relation to how they influence ovecs design.

Pasaru itself is a relatively Earth-like planet in an Earth-like orbit of a Sun-like sun. It is slightly larger, and the day is considerably shorter, but for the most part one can basically consider it to be “Earth but more”. This also extends to geography, biology and of course the basic physics that apply throughout the universe.

Unlike the Earth though, where there are landmasses that are separated from others by massive, impassible oceans, at the present day all landmasses are in evolutionary contact with each other, even before the existence of units and intercontinental travel. Individual islands may still be detached Australia-style, and endemic species and clades2 still exist, but in general things like oceans and mountains do not pose much of a barrier to even biology.

This communicability did not change with the rise of civilisation, and the shallow Edrensano Ocean became the centre of activity of the world, spreading not just animals and plants but also intelligent species and with them ideas throughout the world. Although cultures do lose contact with each other, summing up all available records can reveal that there are enough connections throughout history that at no point is it impossible to route a message from one sufficiently powerful individual to another, though whether such a communication is probable is a different story.

Upon this backdrop of easy contact and relative abundance throughout the world, we can now discuss the intelligent species in question, which developed somewhere in the forests and grasslands of temperate southern Ordžojan and then spread from there.

2.1 Species

The single intelligent species that lives in the world of Pasaru today is called kilis (sg., pl. invariant or “kilises”). For the purposes of this article, one can consider them as being mostly human-like especially in terms of basic anatomy and to some extent even psychology.

The primary difference that kilis have against humans is that they’re somewhat taller and heavier and have six limbs, the upper four of which are arms and the lower four of which are legs. The two in the middle are classed as both, though they are not as good at being either as the other specialised limbs.

The other difference that should be taken note of as it is relevant to the design of flags is the kilis colour perception rules, which is subtly different by way of the fact that kilis have a somewhat wider colour perception range and an increased number of cone cells to accomplish this, as seen in table 1.

| Cone cell | Colour | Peak signal (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| Very long | Ochre | 690 |

| Long | Red | 580 |

| Medium | Green | 520 |

| Short | Blue | 440 |

| Very short | Tyrian | 370 |

When we depict colour in later chapters, we will attempt to keep the colours the same, with the extended colours being pushed back into the (human-)visible range.

2.2 Culture

It would be somewhat crass to say something along the lines of “Pasaru can be largely divided into seven major civilisations today”, because of two objections that are broadly applicable to planets such as these: first, there’s the problem of defining what counts as a civilisation and what is just a subculture, offshoot or hybrid, which is a source of endless suffering and arguments with no real payoff or answer at the end which ultimately relies on military or political power; second even granting that such an enumeration is possible there is no guarantee that the named entities can be defined precisely, both in terms of what they are, what they have and what they do, and also in terms of where they exist. Add complications regarding the deliberate confusion between empire, state and language, attempts to give civilisations uncontroversial names and uncontroversial counts are ultimately futile.

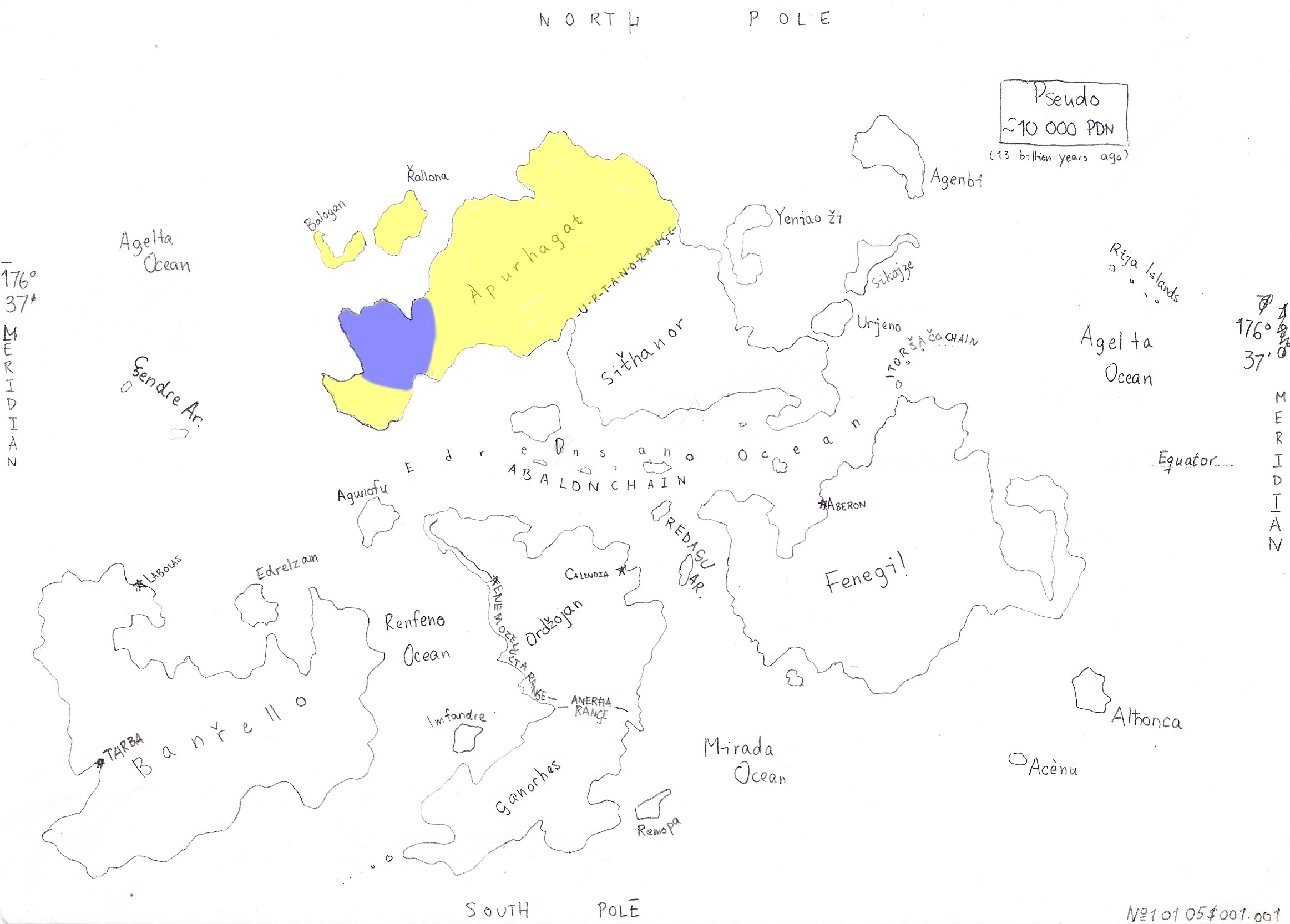

Regardless, just like how on Earth we talk about “Western civilisation”, equivalent names that describe civilisations exist and are used to describe how cultures work in popular terms. So as it is, we will use the following labels to give seven distinct civilisations that together cover a super-majority of all cultures on Pasaru, (37|44) and a very brief blurb for each of them:

- Ordžojan (PO)

- Central civilisation, mostly shallow oceanic. Most powerful and politically at the top of the world; stewards of the International Association of Governments.

- Rattssaw (PR)

- Northern civilisation. Second most powerful; historical rival to Ordžojan civilisation for much of history. Culture converged to Ordžojan civilisation somewhat recently due to extensive contact.

- Agenbi (PA)

- Polar and oceanic civilisation. The source of much record-keeping and exploration in the world.

- Fenegil (PF)

- Eastern civilisation, who also has an alternate name Pfosaj (39|86). Historically a big player, now not so much.

- Bognjel (PB)

- Periphery civilisation to the southeast. Not actually a coherent civilisation but rather a bunch of cultures that are grouped together because the creators of this system don’t know anything about it. Nevertheless, the existence of the label have caused the cultures to converge slightly, more so for externally imposed concepts such as ovexes. It also has an alternate name, Staddo. (39|86)

- Mul dec (PM) (39|86)

- Another periphery civilisation, this one more littoral than deep oceanic and closer to the equator. Again, actually an entire world to its own and treated as one only because the creators of the systems don’t know anything about it.

- Tarba (PT)

- Another periphery civilisation. Mostly known for having languages that behave strangely.

While we will use this list to show how things may vary across the world, keep in mind the massive amount of disclaimers that is needed to create this list in the first place. Figure 2 shows them in a geographical context.

2.3 Language

Unlike the situation with civilisations, the question of languages is much more straightforward and easy to answer, due to a slight difference in psychology that allows languages to become semi-autonomous entities that arguably exist outside of any unit and instead appear as a entity within society as a whole. The details of these are beyond the scope of this article, but they have been written about elsewhere.

Instead of working through the implications of the linguistics situation on Pasaru, we will simply give brief (but more extensive) description for the three languages official for the International Association of Governments.

- Egonyota Pasaru (EP)

The most popular of the three, and of the world in general, E.-Pasaru is a language originating from the Ordžojan (PO) civilisation. Strictly speaking, however, it is a constructed descendent of an older language named E.-Vohalyosun, with the two being more or less the same but for a few of the more irregular parts.

The language is a broadly isolating language with a largely predictable grammar. It has the default pragmatics of the world, meaning that its statistics is the baseline for which all other languages are compared to in terms of pragmatics. This is because PO has become the dominant civilisation of the world. Otherwise, the language is not particularly noteworthy; perhaps because of its dominant position.

Several unusual qualities did make their way into the language, however. One of those is the somewhat mystifying “pragma” system, (not to be confused with pragmatics) which allows for deliberate deviation from the usual language rules by use of special sentences that encode those deviations. This is useful for demonstrating features in other languages. Second, the language is written in a script that has three cases. With the script also being used to write other languages, having three cases allow it to increase flexibility in doing so, though it still takes a Cyrillic approach of adding new letters for each new language rather than using diacritics.

- Rattssaw (Rs)

The second most popular of the three, and the self-appointed representative of the “other world” (i.e. the northern hemisphere). The language is spoken by the scions of the Rattssaw civilisation (PR), which today is represented by the Jesdic Senlis, a semi-large imperial power recently defeated by the rest of the world in a world war. Presumably, its position in the International Association of Governments is a consolation prize for losing. (39|86) (39|89)

The language is the other language that is used to compare other languages to. However, it is notably deviant compared to the modal language on Earth; its phonology does not offer syllables, instead using an alternate grouping called “phonoruns” which affects the placement of vowels and consonants and the prosody thereof. Its grammar is deeply inflecting and has important status and politeness levels, which importantly is non-transitive (there’s no “more polite” and “more casual” levels, as the same inflection can be used for both depending on who says it.)

Rattssaw is also used as a general interchange language across the northern hemisphere, displacing many of the other languages that would been representatives otherwise. There are exceptions, however; the mess of islands surrounding the Yeigon Sea (north of the Mul Dec peninsula in the map above) has three languages that enjoy regional privilege have been shut out of the Rattssaw sphere for this reason. In international relations, they use E.-Pasaru, which is also what we have used for the name of the sea, as it has multiple names otherwise. (39|88)

- Sturp (St)

The third and final language is by far the least popular of the three. It is included in the trio mostly because they were there in the right place at the right time; Sturp-speaking countries, which is basically just Erso (39|86), happen to have a large influence on the technology and the characteristics of the Ordžojan civilisation, to the point where they tend to be categorised as a notable subculture of that civilisation, typically notated PO*.

As a language it is also fairly pedestrian with similar properties to that of E.-Pasaru, but with a few more irregularities and unusual things to inflect by. Notably the language is dominated by intransitive verbs and nouns and verbs tend to alternate with each other in certain contexts. There’s also an entire parallel vocabulary that is only used when compounding.

Aside from Erso, which contains within it several dozen small countries that straddle an uncomfortable boundary between sovereign state and autonomous county (21|37), the language is also spoken throughout Banřello upon which the L.-Erso exists, and in written language it works as a language of interchange.

The planet of course has many thousands of languages, and all of them have their own unique features and qualities which would take far too much time to discuss even at the level we did here. For the purposes of ovexes however, we only need to concern ourselves with these three – the General Ovecs Society is a part of the International Association of Governments, which only has E.-Pasaru, Rattssaw and Sturp as working languages. Other languages, along with the cultures that they attach to, generally would borrow terms from one of these, but it is also possible that they invent calques of their own or analogise with their native equivalents. As such, they are also called the King Languages. (39|89)

It should be noted that the central role of languages in the civilisation and history of Pasaru is not just reflected in their status as near-sovereign entities but also in the fact that they tend to find language in everything. As we will see in later parts, this shows up again when flags start being put next to each other and viewers picked up meaning from this juxtaposition, ultimately resulting in the flag language.

3 History of ovexes

Like flags, ovexes come from a rich history and they have not always been used in the same way as they did historically. In this section, we will explain in some detail how these flags evolved from their original form to the modern form as used today.

As these flags evolved in a history not shared with ours though, it is somewhat more difficult to put them into contexts that can be understood by the prospective reader. To avoid being bogged down by specific dates and minutiae of what happened when, we will instead appeal to a compromise standard that distorts history in Pasaru enough such that if we also distort the timings on Earth history the two can be considered more or less the same. The timeline we will follow is as follows.

| Era name | Landmark time | |

|---|---|---|

| • | Prehistory | |

| | | Formation of city-states | |

| • | Kingdom era | |

| | | Nations start dominating reachable world | |

| • | Imperial era | |

| | | Invention of fast long-distance travel | |

| • | Industrial era | |

| | | Invention of modern international relations | |

| • | Modern era |

It is therefore important to note that this is an ad hoc timing system, that explicitly does away with specific timing and does not say that civilisations have to develop in this way, nor does it say that these two civilisations have to develop in this way, nor does it say that there is only one civilisation apiece in each world. Instead, consider it to be a highest common factor that, empirically, both of the civilisations under discussion happen to follow in that order.

As it turns out, though, that one civilisation in particular invented ovexes, in the same way that one civilisation in particular invented flags, we will pay more attention to that one – other civilisations have their own identification systems, but they are overshadowed by ovexes eventually and are not the focus of the article anyway. With that understanding in mind, we can discuss the history of the ovecs.

3.1 From the castle to the road sign

The very earliest objects that can be found in history that resembles the modern ovecs is the battle standard. These are first invented some time in the beginning of the kingdom era, and they already possess much of the qualities that characterise the modern ovecs: they are boards of a solid, rigid material that have paint added to that material to make it distinct from others. They are also attached to a long pole, which at the time is held by the standard-bearer but can also be planted into the ground.

However, battle standards were (and still are) different from modern ovexes in critical ways: they can have many shapes and sizes, they lack the legend which is mandatory today, and of course they are not meant to represent anything other than that particular army unit or the country it belongs to. They may also sport additional detail that is not allowed on a modern flag, such as metallic decorations at the top.

These were eventually transferred into the entrances of castles and other similar buildings that hold seats of power. This ultimately serves to provide two sorts of information: what the building attached to the proto-flag is, and who it belongs to, all without resorting to the written word. Eventually, these purposes are split into two, one to form an “identity sign” and one to form an “affiliation sign”.3 The identity sign in particular gets to be in the shape of a rectangle with the top two corners cut off; the shape helps distinguish it from the rectangular bricks. (39|37) Because they identify something, rather than be a symbol of ownership, they are placed close to a doorway or a wall.4

These proto-flags also tend to be fairly simple in design; unlike their battle standard predecessors, they are occasionally ordered in bulk, and manufacturing capabilities of the era are rather limited. As such they tend to be simple monochromatic designs utilising only curves and straight lines. Although in modern times things have become much more complex and developed, this spartan beginning is the basis of much of modern ovecs æsthetics.

Over time, the identity sign became more accessible to the average unit, to the point where even very small settlements with populations scarcely over 12 and even individual enterprises can get their own (22|26). So commonplace they have become that they start to resemble regular signs rather than specialised flags, and as it turns out the ruling class was completely incapable of preventing this from happening.5 Or perhaps they were uninterested – these signs do not require one to read to understand them, and keeping the population illiterate has been known to keep them compliant to some extent.

Additionally, later in the imperial era when navigation became much more important, these identity signs became landmarks, as well as being used for finger post signs. Eventually it cottoned on to the leadership level that they had to do something to manage the large list of flags and so the octagonal shape was established as the meaning of “official”. This can mean that it was part of some government, or otherwise “blessed” by a governmental agency as a correct flag.

By this point the proto-flags are almost in their modern form, though there remain crucial differences. Chief amongst them is the lack of a legend, which we will cover in the next section, and the existence of flags that cover still more mundane things such as dangers on the road. The latter is a heritage of their road navigation days, and today they are the reason why road signs indicating danger (17|23), amongst others (17|26), are octagonal.

3.2 Early attempts at internationalisation

Now we are in the imperial era, and as history turns out the civilisations that won out massively happen to use ovexes as their primary identification device. Of course, if they weren’t, we would be describing something else. Even before that though, some of the problems with early ovexes have begun to show, which are gradually fixed here.

The most pressing issue when it comes to internationalisation is that simple flags are in high demand and they are also by definition in very low supply. As such, multiple entities happen to have near-identical designs. On Earth such collisions are actually not that rare – consider for example how Monaco and Indonesia have virtually identical flags, and that’s before considering lower-level divisions that have their own flags – but while it’s mostly tolerated on Earth such collisions are much less acceptable in Pasaru. The solutions that solve this problem form the primary way that ovexes distinguish themselves from other identification strategies.

The most conspicuous fix to this particular problem is the inclusion of a legend, which are two or four extra letters that are put underneath the flag. These letters form a short code that also represents the entity in some way or another. Originally, deciding what code to use was only on a pair-by-pair basis; over time the codes are handled in an international basis through the fledgling International Abbreviation Society, which is an international academic effort to coordinate precisely this: short alphanumeric codes that are associated with concrete entities.

On a sub-national level and also on an individual level, this kind of thing is handled by adding an additional flag underneath the original, representing that the flag below owns the flag above, or that the flag above belongs to the flag below. This is the origin of serial many-mounting, which we will discuss in a later chapter.

On the most local level, that of neighbourhoods and towns, governments have instead did something different. Instead of giving every one of these real flags, they instead just put a bunch of alphanumeric characters on an octagon and called it a day (22|26). This is the origin of the route shield on road signs, and it is why destination numbering6 is popularly used in Pasaru even today.

The other thing that needed to happen to achieve internationalisation is to convince other civilisations to subscribe to using ovexes, and this was done in the conventional way – that is, through a large helping of war and conquest, with a small sprinkling of negotiations and trade along the way. At this point the world is deep in the industrial period, and contact between very faraway places is now fairly commonplace, so all that has to happen is that civilisations and their countries are “convinced” to use ovexes as a way to identify themselves.

Although a good bunch of this “convincing” is done by threat of violence, there is also a minority of civilisations that simply adopted it without such threats. This is primarily those that are already in constant contact with the Ordžojan civilisation so they would adopt it to assist in relations. Examples of these include the Rattssaw civilisation, which adopted it primarily to emulate the at-the-time-more-prosperous Ordžojan civilisation, discarding their own methods of identification in part;7 and the Tarba civilisation, which never saw the need to do something like this in the first place and only adopted it because the L.-Erso to the east had required it as a pretext for communication.

One way that the ovecs managed to make it through to civilisations that do not necessarily welcome them however is its base appeal; unlike most other rival methods, an ovecs can and does represent very small entities that do not pose much of a political threat to a country. The primary tactic here is that these non-threats adopt ovexes, which gradually became a trend amongst the larger community, and this bottom-up “infiltration” gradually made it so that the practice became acceptable throughout the society, leading it to be adopted by the top levels. Though they may have their own methods of identification, these ultimately became secondary through the simple use of overwhelming force and economic power which the Ordžojan civilisation wields.

3.3 Establishment of the General Ovecs Society

The modern period started with a global war of some kind that ultimately gave rise to a large reshuffling of the balance of power. Notably, the end of the war established a super-government of sorts that greatly resembles the United Nations in many ways – both are established with a view to reduce the amount of wars after the world was torn apart by a global war; their member states are to surrender a portion of their power and be bound to their rules to increase international cooperation; and both power over enough people to become a credible threat.

Despite the similarities, the International Association of Governments (flag depicted in figure 3) has significant differences from the United Nations in other ways too. Chief amongst them is that it originally started not as a political grouping but an academic one (39|105), and it shows in many ways. This is why half of its mission is to “catalogue the world”, which is a primary goal amongst academics at the time. Of course, the other half is “managing the ‘unitàge’8” which is extremely political, as it involves the governance end of the organisation, which includes military means. There’s also a wing to handle competing blocs of supra-national organisations, which there are plenty in Pasaru politics.

Still, it is the academic wing of the I. A. G. that handles the keeping of records in the system, and this is particularly relevant for ovexes due to their extensive reach in all levels, political or otherwise. The organ that usually handles associations between arbitrary abstract concepts and concrete representations thereof is called the International Abbreviation Society (I. A. S.), which already existed prior to the beginning of the modern era. In turn, they adopted the at-the-time-obscure group called the General Ovecs Society (G. O. S.) to create a database of existing flags and to set up rules on how to design and make them.

The G. O. S. is therefore the generally recognised “official source” for all ovecs-related matters, including the things that are ovecs-adjacent like the flag language and flag-mounting designs. The people working in the Society generally spend their careers checking minutiae for individuals and organisations who are particular with their practice, which is a surprising subset of civilisation in this case.

This brings us to the present situation, which we will spend the rest of the article discussing and describing. However, there is one final thing that needs to be noted before we close this part: just like everything else in the modern, international era, there are rival and competing organisations that also claim to be the standard-bearer; some of them are affiliated with the I. A. G., but others are not, and they all have overlapping jurisdictions – while most of them only claim regional influence and act as a “supplementary group” to provide local liaison and guidance, some do claim to be the overriding standard for the whole world. For the most part, these groups are describing the same patterns in the world, so while there are differences in detail they do not disagree with each other too distinctly. This article is written in terms general enough that the differences are generally hidden from view most of the time. However, if there are places where such difference are insurmountable, they will be called out as they occur.

Footnotes:

In this article, we use “unit” as the term to cover any entity or group of entities that act as one which participates in some society. This is analogous to the equivalent word in E.-Pasaru ulún, as well as to generalise and cover over the differences between different species, which even terms like “people” cannot necessarily hide.

In Pasaru taxonomy, there is only “the clade”; there is no “level of clade” like kingdom, phylum, &c. This means that each name is just a node in a large (more-or-less) tree. There are only two special types of node: the root node which in principle represents the common ancestor of all extant life, and species nodes which are nodes that have no descendents (yet).

Today these are basically unused except in the case of historical re-enactment.

We will learn later on what symbol is used to assert ownership over a plot of land, but nevertheless it should be clear from here that the stereotypical “stick flag on ground → owner of flags owns this land” metaphor isn’t quite the same here.

One of the more enduring questions of society is how to manage power amongst its participants. In Pasaru is done, though without much conscious effort by any party, through language.

A deep elaboration is beyond the scope of this article, so here’s a brief explanation of how it roughly works. usually called a “king” or similar, wields a language at a particular population. The population can choose to accept that language and with it the rule of the king, but at any time they can also choose to reject the language and cause the king to lose social power (and then real power, via the military). The aristocracy therefore consists of highly charismatic people that can influence linguistic trends (37|41).

One of the more interesting consequences is that electoral systems rarely survive very long in Pasaru (20|39), but on the other hand the people still wield enormous and real power over the monarch who ignores that at his own risk.

Destination numbering is the practice of giving places route numbers, rather than routes, in the context of road, rail and other transportation contexts (16|36). Routes are instead named as pairs of numbers.

The Rattssaw civilisation also has ways to identify themselves historically, which largely revolves around letterheads and words stretched across doorways. They also use a high-mounted beacon as a solution resembling a lighthouse, which is an inspiration to the modern practice of “bar code flags”, a topic we will discuss in later chapters.

/ju.ni.ˈtɑːʒ/; this word is more or less a direct calque of the word “ulúnv̲ĭf”, meaning